PHOTOBOOKS OF NOTE 2019 - CAITI BORRUSO

"Every art-related book I purchased for myself in 2019"

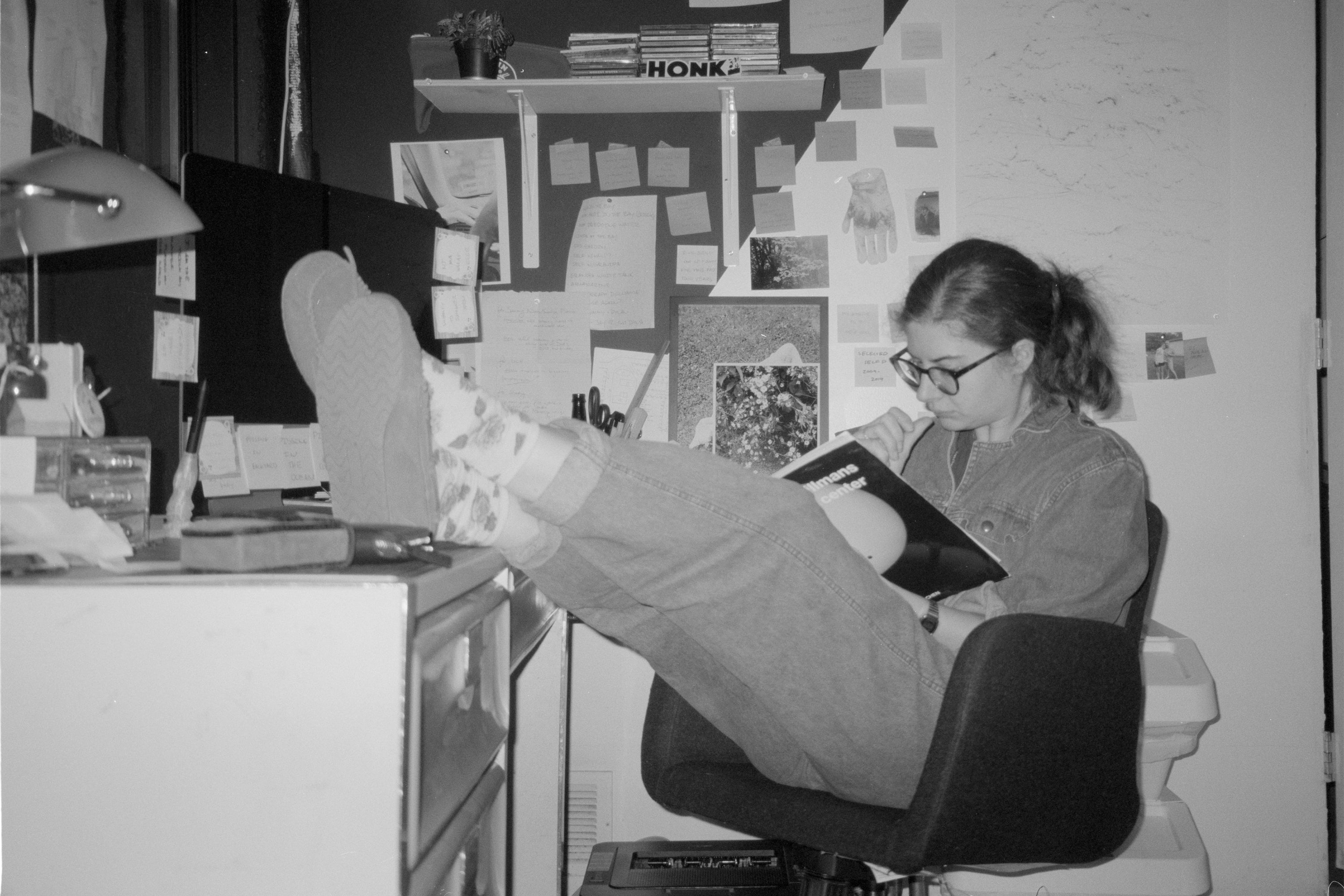

I didn’t buy many photobooks this year. I work with books; I handle them, sell them, stack them, ship them, wrap them, smell them, finger them, daily. Sometimes I publish them. Sometimes I publish my own. Part of my job, technically my title, is to handle the endless submissions of photobooks that flow through our shelves, to parse what is new and good, and it is exhausting, and thus we don’t do it often. Today, instead, I will make a list of every single art-related book I purchased this year for myself. I’m exempting ones I was given, ones I purchased for my graduate program, ones I worked on. And I am admitting I will probably forget some that are hidden at the moment - it’s late here.

The Coast, Sohrab Hura, Ugly Dog, 2019

This isn’t the first book I purchased this year but the one that stains across the year for me. I was excited to know that a new book of his was coming - the title of his last, Look It’s Getting Sunny Outside!!!, and its format, like a library book all blue and joyous wrapped in plastic that curled around the corners, exuded tenderness. It asked to be handled, to be placed on a bedside table, to be loved like a member of the family. I couldn’t afford one then and I certainly can’t now. But The Coast, which came in familiar-smelling boxes from a printer in India we’ve used, pale cardboard and staticky foam, did something else. It expanded past Hura’s family and past an interior and into the endlessness horizon of the water, and the trick of repetition that also expands. Every image repeats once, again, on the following page, but this time with a new companion. It’s a gift that Hura has given us: seldom are we allowed to see a photograph in, physically, the same light, but anew. It feels like something is wrong, the first time I flip through it, the way the images repeat. (I feel like I’m missing something, like I’ve been thrust into a new game without the rules.) And my head moves back and forth, and I flip back and I flip forth and they begin to build. And while I am away for a month, with hardly any books on hand, I can’t stop thinking about it, and I buy one as soon as I am home. I tell everyone to buy one. (I was correct to buy one, yes, because it won the Photobook of the Year Award and now the prices have skyrocketed, but I was also correct to buy one because I still can’t stop thinking about it, which is the right reason to buy a book.) The cover, which echoes a Kerry James Marshall painting, and the back cover, two hands in mottled shades - purple and teal and orange and white and pink and there are so many colors in these hands - they appear in sequence together, for one breath, before each sprinting toward another image, toward another life on the page. Left page, a couple embracing on a cushioned bench, their shadow a third head, right page, the uncropped face in darkness with yellowed teeth and necklaces and the bluish sheen of a polyester shirt. Left page, those hands in all their colors, right page, the uncropped face in darkness with yellowed teeth and necklaces and the bluish sheen of a polyester shirt. Left page, those hands in all their colors, right page, an upside down image of a right side up face in a mirror, looking toward the hands, flecked nail polish on the hand next to it, and pinks and pinks and pinks, the magenta fuschia floral of the dress and the mauve of a fringed fabric on which the mirror rests, the pearliness of a tupperware lid. I could write the whole book this way, its volleys. The first short story sits next to the first image, of someone showing their eyeball to the camera. The last eleven sit sandwiched between an image of the sea at night, where bodies have just been, and two images of women clutching each other in the water, seemingly going their own ways, almost, but not quite, mirror images of one another. Hura has made something magnificent, self contained, expansive and sprawling, self-referential, joyous, exciting.

I mostly read books by women this year, not quite by choice but by molecular guidance. I missed all of the events surrounding this book due to the very systems Winant critiques in the essay of this book, which runs like a ticker-tape along the bottom of each right-side vellum page. Reading an essay in this way, line by line beneath images of women that are made by women, for women, with women, makes me feel breathless, tripping over myself to have more: more of the words, more of the images, more of the feeling itself. The grand theme of the year in reading that has slowly revealed itself to me has been women, not only seeing themselves but writing themselves and depicting themselves. Women in their own bodies, and myself in mine. The book opens with a haircut, a mirror, the hug of exposed ribs, socks high above the tops of boots, and the line, Is it possible to leave everything behind? The photographs that follow, the photographs of photograph making, of circles in woods and joy, of depiction and recreating language, of photographing to photograph to see to know to make outlines of what did not exist, the photographs serve as proof. And they serve as proof for nothing, no one, but the women in them, and the women to follow. All these naked bodies, unabashed: together, occupying desire, discarding shame, embodying a state of threatlessness. How does it feel to live without the looming threat of sexual violence, harassment, or trauma, without occupying a body that is also a weapon and a minefield? asks Winant. The images are from the early eighties, a time when women flocked west to create these photography workshops, these new languages, but Winant binds them together in an object that brings us to the present day, to the same feelings anew. (I have to stop writing this because I have begun to cry.) The book ends, I might add, with another haircut, this time depicted by the one whose hair is being trimmed. Her face is warm. She looks at herself in the mirror expectantly. She holds the camera as though she knows it. The barber lays a careful finger on her ear, folds it forward, to trim behind with the buzzer. I can hear this picture; I grew up inside this picture. I wish, forlornly but with hope, cautious hope, that I had grown up inside the rest.

Showcaller, Talia Chetrit, MACK, 2019

When Talia came for the signing her stomach was round with promise but I offered her wine regardless because there is no kind way to ask if one is pregnant. She denied the wine, laughed in a sweet way, and signed my book for me. Her photographs have filled me with a sort of rampant jealousy, and now I am jealous for the images she might make of her pregnant body, of her post-pregnancy body, something I am not sure will have a place in my own future. (Like the voice of Veruca Salt: I want to photograph myself having sex outside, and I want it NOW.) The way Chetrit depicts herself is not often flattering but not grotesque; it sits somewhere in a middle ground, possibly erotic, possibly pandering to onlookers, possibly none of these, and she doesn’t care. She leans backward against a tarp that crumples beneath her weight, one hand flung up for protection, her face stilled. There’s a lot of editing questions I have for this book, as I often do with books published by MACK, but Chetrit’s self-portraits shine for me. They offer me new ways into my own body, new ways into my own practice. It is as though, through her work, she has gently nudged me and said, go on, it’s okay, photograph your vulva. (And photograph my vulva I did.) It’s the last image, though, that hangs in the air: a bulb shutter release, squeezed between the upper thighs, the tiniest patch of pubic hair above and the endless flesh of body below, the umbilical cord of the camera making a reflected triangle with the crease of the leg, utterly recognizable and yet completely foreign. I try to make this picture. My thighs are not strong enough.

Somewhere Someone, Cynthia Daignault and Curran Hatleberg, Hassla Books, 2017

I often talk shit about certain aspects of books and then come later to eat my words, which is humbling. This is one of the books I’ve acquired latest in the year; I traded Hatleberg’s book Lost Coast for this one, which was created with his partner, Cynthia Daignault, and functions equally well as an installation and a book (rare!). Somewhere Someone, which takes its name from a John Ashberry poem included on the endpaper, of which there is technically only one, or maybe it is just the bookboard. Forgive my book terms as they start to feel messy with an accordion book, which is the aforementioned shit-talked component of this book. For this project, though, it is the only thing that makes sense. Daignault and Hatleberg hurtle toward one another from opposite coasts, meet briefly in the geographic center of the country (a nondescript cornfield in Kansas), and continue on the exact same routes to hurtle away from one another. The black and white photographs are unassuming at first glance, but the loneliness and gentleness of them, and of the entire project - a project about driving, and love, and the vastness of America, as any project about driving and love is wont to be - and the parallel unfolding of them, physically and metaphorically, is magic enough. I saw the installation at Mass MoCA at the tail end of 2017 - in which two slide projectors are pointed at one another, continually showing images the other can’t see - contemplated buying the book, and didn’t, possibly because I was sad and lonely at the time, or poor. (Even more regretfully, I emailed Daignault earlier this year to see if I could purchase a copy. She never emailed back. I still feel embarrassed about this.) The Ashberry poem calls to mind the sorrowful words and strums of Daniel Johnston, who died this year: True love will find you in the end / This is a promise with a catch / Only if you’re looking can it find you / ‘cause true love is searching too / But how can it recognize you / Unless you step out into the light, the light? Daignault and Hatleberg conceived of the project as partners on opposite coasts, but as they undertake the drive, their lives - and their drives - begin to look like one another’s, until they have met and switched. They have looked for one another. They have aimed directly at one another. They have kept going.

The Love in Sex Life, Sha Kokken, Ikeda Publishing Co., Ltd., 1970 (third edition)

Technically this is a manual for freshly wedded, heterosexual couples to use on their wedding night, to guide them through first fornication. There’s a larger version of this book that is bound with spiral inside a slightly puffy cover, and really looks like a Manual. I have the smaller bedside version, which has no puffy cover or spiral and costs less but still has funny, sort of sweet photographs in it. There is no nudity in the book and no men; a woman clothed in various leotards and tights poses as both the male and female partner, on separate halves of the page. It’s almost a flip book, with pages cut in half; there are mix-and-match equations for sex. I buy it, semi-jokingly, to use with my partner, but most of the positions are fairly benign (i.e., not necessarily positions that require flash cards). There’s something to be said for laying in bed together and reading aloud the descriptions of each sex position, which are dated and goofy. The description of missionary: This posture should be used as a relaxing pose rather than a moving posture in view of the fact that it gives the woman less freedom of movement. But it may satisfy her motherly instinct. It is not suitable for corpulent women. I think we gave up on using it as a sex guide fairly soon, but now that I thumb through it again, I’m reminded of how much I genuinely like it as a book.

CICORIA. A brief account of Alessandro Cicoria’s life and work, Alessandro Cicoria, NERO, 2018

I am a sucker for photobooks that look like novels, that are pocket-sized and don’t demand protection of any kind. Alessandro Cicoria’s vaguely self-titled book is just that; a big black cat in a tree yells from the cover. The caption for the first image is South Pier Giuolianova, photo from 2009 remembering myself in 1993. Most of the images are full bleed, and the paper stock switches from uncoated paper - almost that of a paperback - to something magazine-like and coated. There are captions in sort of big text, but not for all. This book makes little sense to me and I love it. (I could probably make more sense of it - there’s an interview I haven’t read yet - but I think it depicts the beginning of his studio, Studioli. It was published on the occasion of an exhibition of the same name at Vin Vin Gallery at Ruyter Studio, Wien.) There are photographs and photographs of objects and a few collages and drawings. Whatever it is, flipping through it brings me joy, and I find something new each time - a shape repeated, a color distorted. It sits next to The Love in Sex Life on my shelf.

Laments, Jenny Holzer, Dia, 1989

Another small, compact book, also published on the occasion of an exhibition. This contains thirteen texts inscribed on stone sarcophagi. I remember not really knowing who Jenny Holzer was but understanding that her words were important, and buying a book about her for a distant friend’s birthday in college. (I remember touching one of her stone benches at Mass MoCA the same day I saw the Hatleberg/Daignault installation. I traced my fingers over her words. I wondered if anything I wrote could be permanent enough, good enough, to carve into a bench.) This is the first Holzer book I own, and it’s another book that feels adequate as it is: small vellum pages, with small text that looks as though it should be chiseled into stone. It is exactly what it is. I’m glad this is the only Holzer book I own, instead of something big and mass produced; it feels right.

The American, Jason Polan, self-published, 2019

I could write more of an essay about Jason Polan’s energy and the way it has impacted me than I could about Robert Frank, whom this book is an obvious, and perfect, homage to. Jason has a knack for showing up at precisely the right time (to Dashwood, where I encounter him the most, but also to all of New York City, or maybe this is just a gift of his - to see what needs to be seen), and arguably the publication of this tiny book was done at precisely the right time; Polan and Hans Seeger, the designer, managed to produce this in four days in time for the book fair after Frank’s death on September 9th. Frank lived around the corner from Dashwood, and I didn’t ever bother to go over and see him nodding out his window; I assumed, foolishly, as one does, that he would always be there. The American, one letter off from Frank’s first, and widely published, book, takes the same ratio as the original, but smaller, with an inverted cover: Polan’s uneven, warmly familiar handwriting in white, on black cover stock. I could sing the praises of his drawings, but it’s the short essay he writes at the beginning, and the details - the drawing of Frank’s door, number 7, on Bleecker Street, two days after, and the drawing of his hands on the cover of the book when you take the miniscule dust jacket off, and that 7 again on the first page. Frank was a well-loved and important figure, but what makes this book so generous is that it was made by someone who also loved him. Polan’s notes - I’m pretty sure this is Robert Frank. 2.5.2019 It is. - and his marks, his details - the slow nod of Frank’s head as he leans forward for a nap on the summer solstice of 2018, a taxi number, the cross-hatching of the shadows around his door - there is no artist better, no human kinder.

Caiti Borruso works at Dashwood in NYC as the Submission's liaison. Most likely, if you ordered something from their website... she packed it. She also runs Elementary Press, a great small press out of Brooklyn. She is also getting her MFA at Image Text Ithaca... which is gorges. Caiti is very busy, most of the time.